Digital Omens: Art, Technology and NFTs

Digital Omens: Art, Technology and NFTs

By Drew Haller

The contemporaneity of the RMB Latitudes Art Fair manifests itself in the QR codes set underneath each artwork, and the 5G Rain Boxes coloured with the same tonal palettes as the artworks they offset. With accessible high-speed wifi, the fair floods Instagram feeds throughout the weekend. And, as always, there are the content creators and art influencers, who experience the fair through their digital proxies.

Beyond the photo-opps and ritual chants of hellohowareyous, one can fall into USURPA Gallery rather by mistake. The treasure-hunt map that outlays Shepstone Garden’s mythical setting makes it easy to get lost amidst corridors, halls, retrospectives, talk rooms and dove houses. But one unassuming staircase will take you to USURPA’s sunken booth, where you will immediately be awash with quiet. The exhibition sits below ground in a cave-like domain, free of windows and somewhat cooled by the stone surrounding it. The space is dimly lit by blueish-white light emanating from the arched recesses, whose hollow holds the curiously flat Samsung Screens that display digitally rendered artworks. There is no wall text, only a sign that reads DON'T LOOK BACK. Across the way, a hashtag shouts #AFRICANOPTIMISM. At the centre of the room, Nandipha Mntambo’s bronze sculpture has awakened, craning its anthropomorphic neck to gaze over its shoulder, the light catching its jagged vertebrae, wet with high-resolution finishes. The beast awakens, and the inner child stirs. So does the digital alarmist.

The first of its kind in South Africa, USURPA is a digital gallery that works with technologists and animators to awaken idle artworks. At such an event, the dynamic screen feels somewhat out of place, an omen of change.

African Optimism

Curatorially, the exhibition is aspirational. Its star-laden programme features changemakers like Samurai Farai, Justice Mukheli, Katlego Tlabela, Cinthia Sifa Mulanga, Nandipha Mntambo, Mark Modimola and Sphephelo Mnguni. For most, this is their first time producing multi-media NFTs, moving beyond the static to engage with the disputed world of cryptocurrency.

In Tlabela’s work – known for its manifestation of African affluence and the robust interiors that define capitalist success – fireplaces crackle, a young man's head bows, and the Doberman keeps watch. ‘Rich Ni**a Problems’ is a living lightbox that reveals the unexpected complexity of wealth and success. At the edge of the room, Mukheli’s shadow is in flux, his movements tracing an echo of light, his body morphing and bending to better understand its own masculine shape. That same movement pulls into Farai’s artwork, which reads like a neverending process piece.

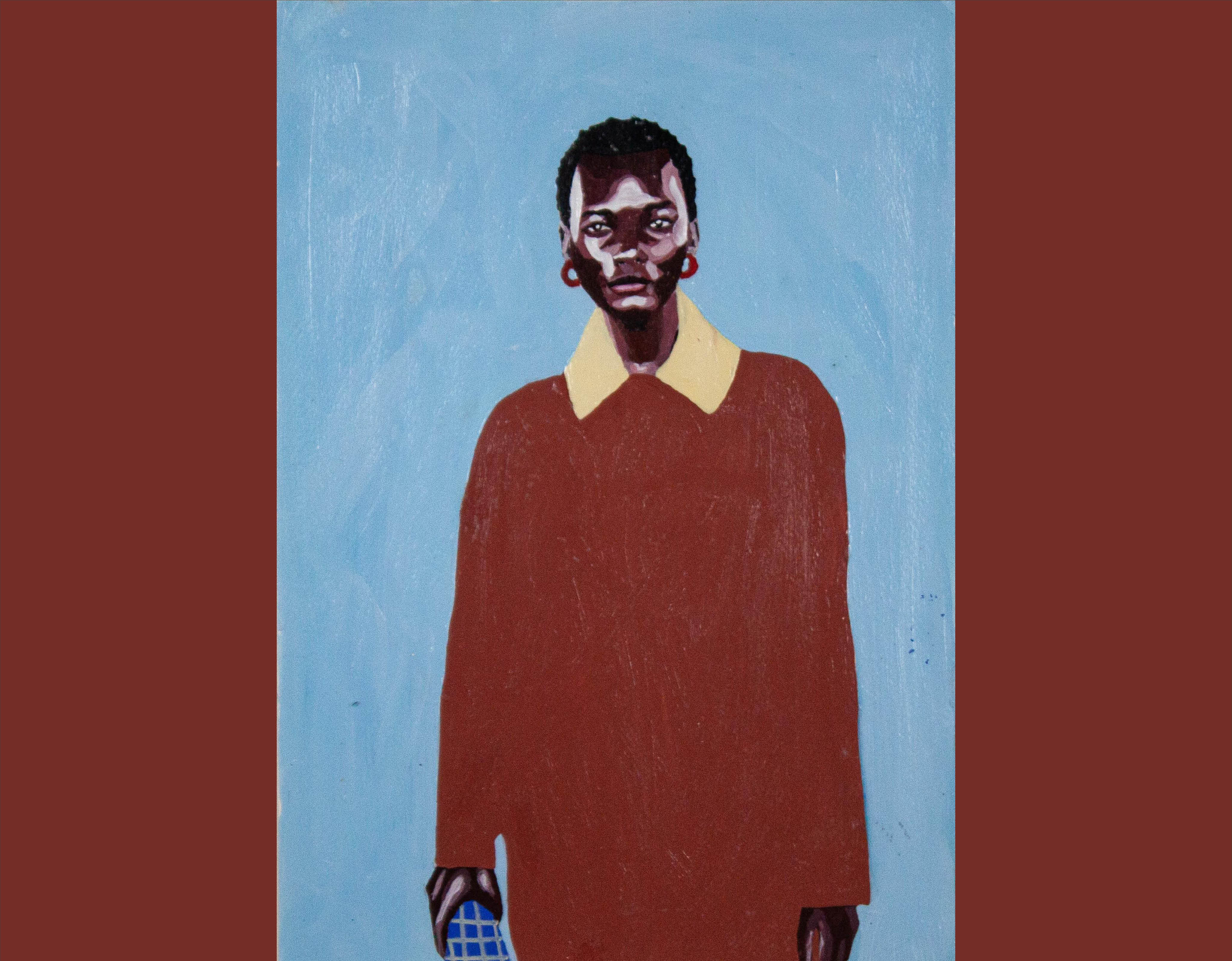

Each articulate line expresses itself loosely to form two bodies finished with horns, the same horns worn by Mntambo’s revitalised sculpture. The artwork continues building and layering until it is totally covered in opaque white – like a decision to start over. Its urban style is mirrored in the setting surrounding ‘Thandeka’, a Durban woman whose lighter sparks as she gazes at you with contempt. Mnguni, known for his rich but muted portraiture, brings one face-to-face with the strength of a woman in the metropole. On the softer side of the dialogue, Mulanga’s work shakes and lifts, collaged elements moving like stickers in a child’s hand as she shifts her dollhouse accordingly. Finally, a boy standing on a lone platform tilts his head upwards. ‘No Man is Born Wise’, offers a reminder that upliftment comes from a willingness to learn, to seek out knowledge. In its totality, the exhibition invites you to contemplate the nexus of African culture, identity and modernity.

Modernity has, for centuries, been a force imposed onto Africa. One need only spend five minutes at an art fair to know that the dialogues surrounding contemporary African art are those of reclamation, representation, and the search for renewed agency. In a culture hybridised by centuries of unequal trade, slavery and migration, it is unsurprising that African artists have focused so heavily on empowering themselves as storytellers. This is a means through which we can imbue the abstracted bodies that fill canvases with meaning, using narratives above those of experts and academics who write history in foreign tongues. As Edward Said says in his book Orientalism, “A very small but definite function for the humanities: to represent humane marginality, which is also to preserve and if possible to conceal the hierarchy of powers that occupy the centre.” USURPA attempts to do just this.

Director, Kokona Ribane explains, “Our mission is to curate and showcase both established and emerging talents, embodying a distinctive African aesthetic on a global scale. Their creations warrant acknowledgement not as mere novelties, but as essential elements of contemporary art. Our central objective revolves around highlighting African art and its creators on a decentralised global platform”.

USURPA returns the power of story to the artist, using the very same technology that has often harmed and dispossessed our society of creatives, crafters, and artisans. Unequal distribution in digital infrastructure has only mimicked the impacts of social and economic injustices. This is perhaps why African artists are so concerned about ownership in the digital age – because its people are immensely familiar with the historical impacts of appropriation, theft and exploitation. How enterprising then, to reclaim the machine to prove one’s own humanity. And how bold, to attempt to shape modernity, instead of letting it shape you. For there is unlikely a better people to set a standard for ownership, not as an exclusivist endeavour, but as a necessity meant to better represent the collective.

Nexus

For its meticulously curated and coherent booth,USURPA is named one of the top 5 finalists in the Lexus Competition. But the win is marred in controversy. Gallerists argue that it is not art for art’s sake, that is irrelevant and trendy. Some artists tell me that they find it frightening, while industry creatives boldly contest the machine’s capacity to translate the human spirit, warning of the threat to their livelihoods. The disagreement is palpable, and the debate over the black box model of NFTs and digital art is full of unknowns. Platitudinous whispers describing cultural loss fill the room.

Lexus Selection Committee judge, Alexia Walker, says: “People are often resistant to the new, and then things subside.” Ribane is unphased. He says, “If there’s a person in that room, and they make people feel intimidated, then that means they have an impact.” When asked about the purportedly unstable digital market, he says, “This is not about NFTs. This is about innovation.” He goes on, determinedly, “Every other form has been passed down to us. But this, this is something that our generation started.” After a pause, “I think about the worst-case scenario. They say we don’t need it, and we go back to what was. It’s not the worst thing.” Another pause, “But still, it feels like a step back.”

Technology has, in many ways, been both problem and solution. Art, conversely, is question and answer. They have previously existed in a binary and served different functions. While technology serves progress, art is expected to serve emotion. To Alain de Botton and John Armstrong, art is a tool that can act as a purveyor of hope, a way to recover our sensitivities, and a guide to self-knowledge. But more and more, we must assess the intersection of the two, in an acceptance of the digital-analogue duality that we inhabit. We are constantly interfacing, looking for immersive experiences to escape the frightening material world in search of the experiential, the utopian, and the transformative. Yet some still fear the unknown.

In 1989, Margot Lovejoy said: “Paranoia about the direct use of technology in art-making is largely due to an old fear (which began when photography was invented) that machines are a substitute for art”. The error in this is the failure to recognise that technology is invented and shaped by humans, who are ultimately responsible for its use or abuse. Should we choose to shape it ethically, the digital can solve major challenges in the art world, including but not limited to provenance, ownership, and preservation. And what’s more, it can be a tool, a means and not an end. As Ribane says, “It’s not overnight that you become a digital artist. There’s a lot of technicality that goes into it, and such time should be valued in the same breadth as a physical painter who understands which brush to use. The same goes for digital — they must understand which tools to use to amplify their story.”

But, as Marshall McLuhan so aptly warned, the medium shapes the message. Should we wish to use the digital to expand the physical, we must seriously interrogate the power held by the makers of such technology, and the ethics around its distribution. In Glitch Feminism, Legacy Russel expands on theories from Donna Haraway, Judith Butler, Audre Lorde and Octavia Butler. She says, “All these internet avatars have taught us something: that reality is what we make of it, and to make a “real life” whether online or AFK (away from keyboard), we must seize it”. USURPA’s DON’T LOOK BACK explores the confounding, the challenging, the potential.

In an interview with Latitudes, Farai says, “For me, an innovator, a pioneer, this is what it’s about. It’s about challenging the boundaries. It’s about challenging the status quo. It’s about pushing against any confines and creating tension with creativity in order to show people that it’s not just possible, but it’s a necessity.”

The increased inevitability of art’s intersection requires us to seriously consider the possibilities, and limits, that come from an exhibition like USURPA. This is perhaps more productive than denying it outright.

Because when a puritan denies technology’s potential in art, we must ask ourselves, is this a frustration with a human impulse to innovate? Or is it a frustration with the uneven power balances that dictate how the digital continues to commodify, obfuscate and shape our culture? If it is the latter, then perhaps our complaints are better suited for those who write the regulations that moderate, regulate and surveil such technologies. Because, as far as the artists involved were concerned, if they could make the picture move, why not?

This article was produced as part of the ARAK x Latitudes Critical Art Writing Workshop led by Ashraf Jamal over the course of the 2024 RMB Latitudes Art Fair.

Writer’s biography:

Drew Haller is an emerging creative writer and researcher. She holds an International Relations degree from Stellebosch University and an Honours Degree (Cum Laude) in Media Theory and Practice from the University of Cape Town. Her intersectional interests have led her to work in commercial art galleries and agencies, as well as non-profit organisations such as the Parliamentary Monitoring Group and creative collectives such as That Eclectic, all while freelancing as a writer and editor for organisations such as Africa Practice and FundZa Literacy Trust. In 2021 she was selected to work with the African Podcast Workshop, and in 2022 she was named a Design Indaba Emerging Creative. Playful, inquisitive, and analytical, she is passionate about the connective power of language. Her non-fiction works investigate social justice issues, human nature, and fringe culture, while her current role with Research ICT Africa allows her to explore the political economy of the media as well as data justice and governance. Drew's primary creative pursuit is that of co-creating zines as a way to facilitate freedom of expression, biblio-diversity, and creative journalism fuelled by countercultural, pluralist values. When Drew isn't at her laptop, you can find her in gardens and galleries, on coastlines and cliff faces, debating and dancing with friends, or preparing family dinners.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.jpg)

.png)