Three afternoons at Latitudes:A Study on Buqaqawuli Nobakadi and Kaleab Abate

Three afternoons at Latitudes:A Study on Buqaqawuli Nobakadi and Kaleab Abate

By Dumisani Mnisi

“A work of art encountered as a work of art is an experience, not a statement or an answer to a question.” Well then Dumisani, what are you doing, girl?

These words by my favourite critic, Susan Sontag, echoed in my mind as I entered the mythical world of Shepstone Gardens on day two of the RMB Latitude Art Fair in Johannesburg. With a hot cup of Mocha, I allowed the glamour and grandeur of the previous day to wear off. The first day of the fair was disorientating. It was my first time at Shepstone Gardens. I was dazed by the grand halls, marble floors, the Herbert Baker architecture and how it all seamlessly complemented the opulent gardens. The people were just as lush, clinking their champagne glasses and smiling with their eyes. For a moment, the performativity of it all deflected the motive of why I am fond of such spaces: the art!

Once I grasped the duality of the environment as a work of art in itself, the intention behind where the pieces are placed and how it influences communication with the art – I felt present and aligned. Firstly, I was intrigued by the dialogue that happened between the art and where it is positioned at the fair, a comment on the structures and the unspoken echelons of the art business. The prolific Nelson Makamo pieces sitting at the Rooftop Pavilion, untitled, daring you with its price tag, question its magnitude, perched by the textile arts from Lulama Wolf, Ditiro Mashio and Reneé Rossouw.

Just next door in the mezzanine, Bambo Sibiya foreshadowed his anticipated solo exhibition Ngema Kokuqubuka – After Precarity' with his explosive work, ‘Jabu Shoulders’ (2024), a compelling painting that stopped me in my tracks. For me, it was the face – the precision and detail in the round nose and full lips, the straight-up hairstyle and golden hoop earrings – the familiarity and resemblance to myself and the women in my life. I was in awe. The painting looked like a photo I would find in one of the albums my grandmother stores under her bed. It reminded me of that one aunt in my family who's cooking always had me licking the plate and asking for seconds. It conjured home.

Sibiya’s use of patterns, vibrant colours and the regality in the garment is reminiscent of the dutch wax fabric in Yinka Shonibare’s work. I was fascinated by Sibiya’s eloquence in creating a space of critique and celebration.

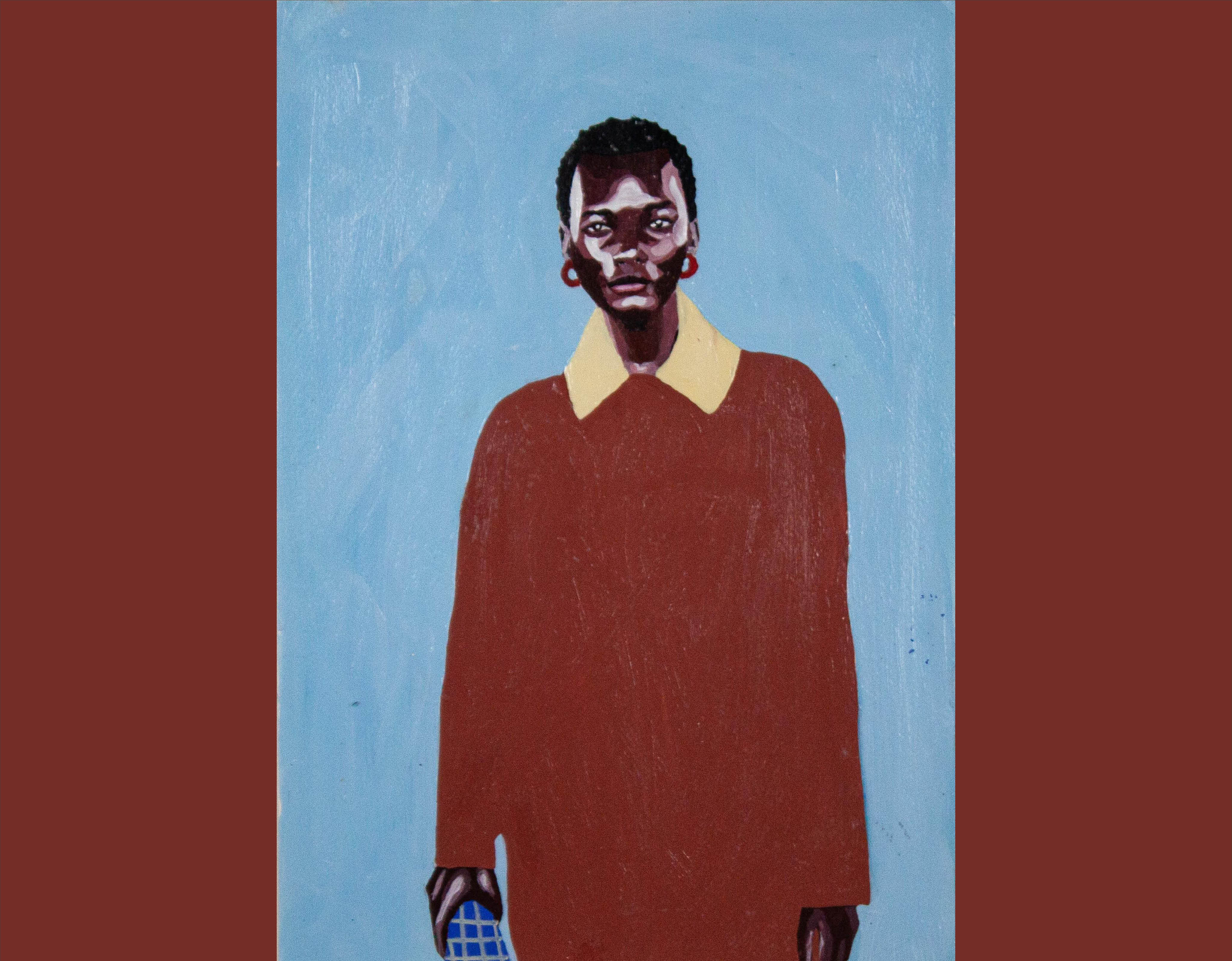

As I made my way through the Centre Court of the fair, digesting the different booths and familiarising myself with the artists and galleries, I was summoned by the work of Buqaqawuli Thamani Nobakade. The resonance of her name was no coincidence. “Buqaqawuli” – which in Xhosa translates to “glory” or “to illuminate” is affirmed in her art. Regality is the theme of her work.

Before I could investigate further on the title of the work, I was captivated by the medium – the texture of the material used denotes luxury and softness. Nobakade layers her canvas with lace fabric creating a multidimensional surface for her subjects. The floral lace patterns embedded in her art act as a lens and manual on how to navigate femininity in her work. This softness translates in her colour pallet as well, using warm hues of browns, pastel pinks and yellows, rich greens and blues, she implores grace and regality on the Black femme subject.

‘Olympia (1863) giving herself flowers: A Reverence for Self Adoration’ (2024) alludes to French painter Edouard Manet’s controversial piece ‘Olympia’ (1863). Manet’s painting created discourse by tainting Venus, unravelling the mythical, goddess narrative attached to the female body. The outrage towards ‘Olympia’ – the verisimilitude in her body, the lack of passiveness in her gaze, her black maid handing her flowers as a form of payment framing Olympia as a prostitute – disturbed the representation of woman as a passive material. It opened up new discourse which fueled the first and second wave of feminism allowing women to be active subjects beyond art.

By portraying Olympia as a black woman, Nobakade acknowledges the erasure of the Black woman as multidimensional in both art and history. She uses this iconic painting and brings it back to contemporary times. Her work is an ode to censored figures like Sarah Baartman who was labelled the “Hottentot Venus”, packaged and shipped around the world – her personal essence and integrity reduced by this “otherness”.

This otherness that I have personally experienced when I travel outside of South Africa to this day. The bouquet of flowers in Nobakade’s ‘Olympia’ are a peace offering to all the misperceptions and nonconsensual discourse framed around Black women. The delicacy and softness in her technique subverts the tension and allows us to see ourselves as the delicate complex beings who do not need to be categorised to have value. Who can just be beautiful, sexy and cool without the “buts” and “ands”. I found it fitting that Nobakade is presented by Under the Aegis, founded by Anelisa Mangcu, a young black woman creating a space that focuses on the intersectionality in African identity.

Kaleab Abate’s ‘Statues with no sculptors’ (2023) evoked more questions than answers. Whose faces are these? Where are the rest of their bodies? There is chaos and distress to the piece that requires unravelling. At first glance it looks like a distorted collage – a layering of cutouts and printouts of nine black heads pasted on European plinths caged in colourful frames. But as you move closer, the work is a flat monotype print. I was intrigued by Abate's technique, the ability to mix mediums, creating depth through paint and drawing then reducing it to a flat finish demonstrating the helplessness and defeat of his subjects. As I moved closer, inspecting each frame I noticed that each face is young and fatigued and the more I observed, I realised I’ve felt the same way more often than I would like to admit.

The youth in Abate’s faces demonstrate the feelings echoed across the continent – a yearning for more and a disinterest in mediocrity. The confrontation in some faces, while others look away in disdain or boredom serves as a defiance to the state of affairs in Africa and the rest of the world.

Statues are symbols of meaning. They are created to commemorate heroes, to carry histories and preserve culture. The placement of black statue heads on plinths is ambiguous, it connotes how the events of the time – the displacement of people has irreversible consequences while the bursts of colour in the background suggest hope.

The title of the piece is just as haunting. A statue with no sculptor means an artwork with no creator, a child with no parent, a generation with no direction and no guidance. This is dangerous. Abate’s work is ground to unpack all the issues the media has become oblivious to. He uses these opulent ‘safe’ spaces, wherever his work might land next – Latitudes, MoMA or the Louvre even – as a podium to announce the unfathomable truths and questions: People are dying, what are we doing about it?

This article was produced as part of the ARAK x Latitudes Critical Art Writing Workshop led by Ashraf Jamal over the course of the 2024 RMB Latitudes Art Fair.

Writer’s biography:

Dumisani Mnisi is a multimedia journalist from Atteridgeville now based in Johannesburg, South Africa. She is a contributor to a number of publications focusing on art, pop culture and society. If she's not writing, she's shooting content for her channel, Breathe, Art, Live - a channel that celebrates African artistry through conversations. She holds a BA Honours degree in Journalism and Media Studies from Wits University.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.jpg)

.png)