Untraceable

Untraceable

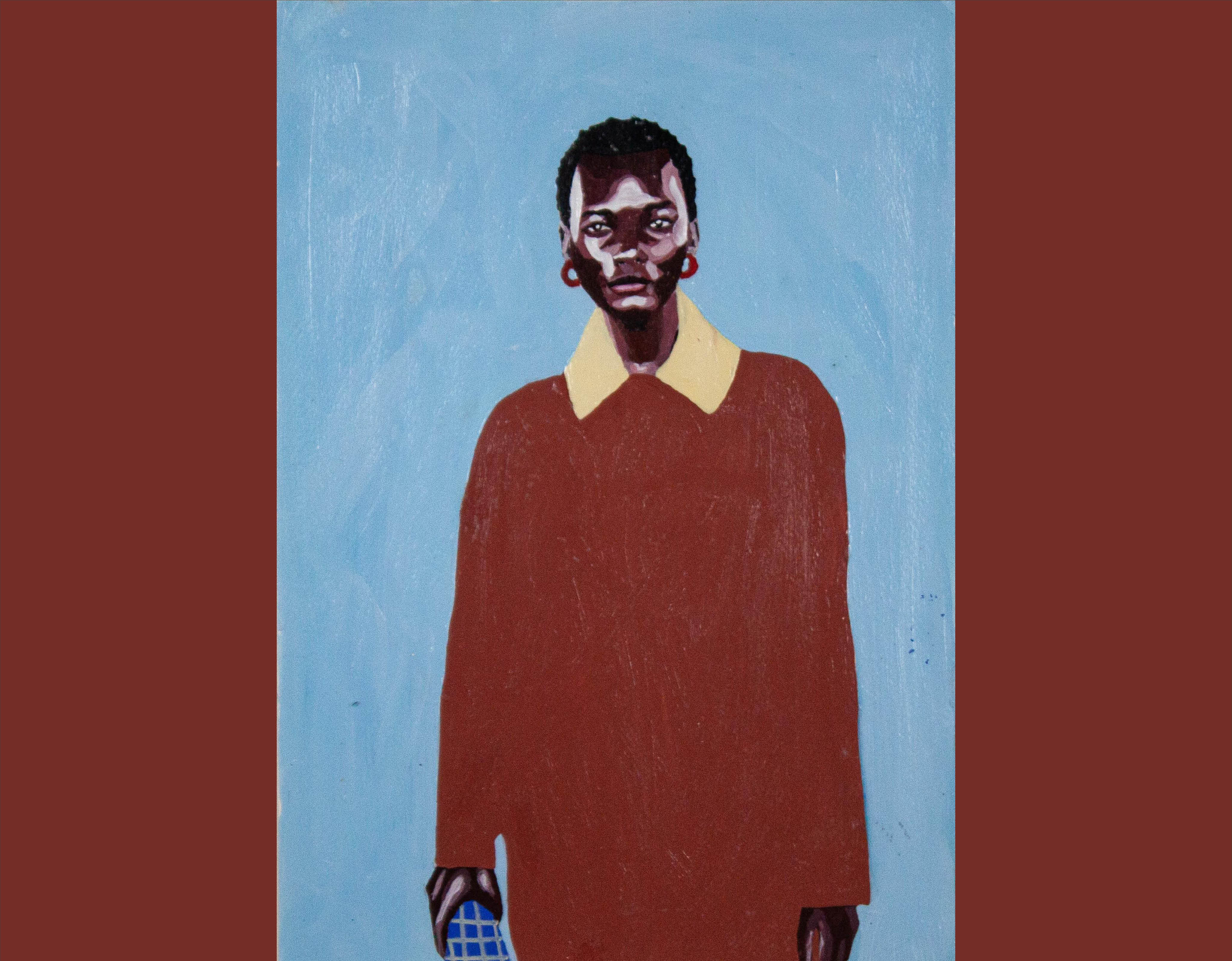

Lukho Witbooi

Mauritius is a melting pot of people with diverse identities, being home to descendants from Europe, Asia, India, and Africa. Born in 1986 in Quatre Bornes, Mauritius, Gaël Froget has created a space of complicated identities and opportunities that immediately transgress boundaries, making his artistic signature difficult to trace.

When Froget first exhibited his work, he introduced the concept of 'Art Vandalism,' where he would appropriate photographs or ads and paint over them. ‘Then I slowly started to evolve and made everything from scratch, experimented with photography and digital art, keeping the same vibe and energy in my work,’ he explained in an interview with Marko Stamenkovic, adding that, ‘in the end, it was no longer vandalism and less fun’. [1]

Froget's reflections on the growth of his practice help us understand his evolution as an artist and his unique place in Mauritian contemporary art. The idea of art vandalism is significant, as it mirrors the issues Achille Mbembe identifies in his essay “The Little Secret”, published in Black Reason (2017), about colonial statues and monuments that persist even after proclamations of independence. Mbembe argues that:

These relics symbolise the ongoing struggle against colonisation. Domination not only affects people physically but also leaves lasting marks on the spaces they live in and their thoughts. It keeps them in a constant state of confusion and prevents clear thinking. This ensures that the dominant authority can manipulate them into acting and thinking as if they are under a powerful spell. The daily routines and unconscious structures of life are also shaped by this subjugation. The dominant power imposes such control that people can only perceive and react according to the authority's influence, making them hesitant and uncertain.[2]

Similar comparisons can be drawn to the French philosopher Bernard Stiegler, who speaks about digital technologies in our lives. Like colonial statues, these tools are social products constructed by humans. Writing about the work of Stiegler, Bryan Norton notes that these technologies ‘shape how we listen to music, navigate from one place to another, and connect with others. These everyday activities have been changed by new technologies and the people who make them. However, we seldom pause to think about what this means for us’. [3]

Stiegler believed that this forgetting is a serious problem for human life in every aspect. When we forget, we lose our crucial ability to imagine different ways of living. It makes the future seem restricted, as if new technology determines it beforehand. [4]

The parallels between the issues Mbembe identifies in colonial statues and the problems Stiegler sees in digital technologies are striking, as is Froget's practice, which is growing to address similar issues in Mauritius. 'After the Art Vandalism phase, I found it important to go back to the base itself: paint,’ he says. ‘I tried a lot of different mediums and techniques, and tried to focus on my own artistic universe. I started to observe African arts and crafts, which are part of my culture, with the idea of creating something personal from those influences’. [5]

Froget claims that, in Mauritius, art is not something the island's inhabitants take seriously. Despite these obstacles, Froget intuitively understands that something distinct can emerge from the remnants of the past. Engaging with his works in the ARAK Collection, we can map a world that speaks to the present moment and possible futures.

.webp)

In Untitled (2023), one sees his artistic signature — a sense of being untraceable; an artist articulating and exploring new frontiers. This artwork depicts a palm tree with a black and orange trunk, outlined in blue. The palm tree also wears glasses and a hat. In the background, there is a red tree, and the rest of the paper is composed of a variation of colours like green and red, conveying an island-themed aesthetic.

Movies greatly influence our perception of islands. The beautiful beaches, natural light, and the meeting of ocean and land, make Mauritius a very attractive tourist destination. However, a question arises about how Mauritians respond to the outside world's influence, which has also begun to shape their self-perception.

It appears that, due to modern influence and historical factors of origin, the spirit of Mauritians is disembodied. Speaking to Froget, the artist claims that despite their diverse heritage, Sega music speaks to all Mauritians. While listening to the music, I find it surprising how the song samples ocean waves, but then I realise this gives a unique perspective on Froget's art.

Considering that the island was uninhabited until 1638, it becomes clear that, as an independent democratic state, there is a desire for a more stable sense of national identity. The artist appears to place this spirit into the land and palm trees. Just like the ocean waves in Sega music, we find in his practice an honouring of nature. This speaks to the first stage of nation-building, where unconscious forces are projected into nature, allowing humans to forge a more harmonious connection to their environment. It creates a space where Mauritians can exist with clear thought that speaks to their own sense of being.

'Art is not something that is celebrated in Mauritius, and unfortunately, most homes here don't display art. It's not valued. But I think it's important for my children to be able to communicate their heritage to outsiders in the future,' Froget says. Thus, the artist seeks to 'fill an emptiness that stems from a feeling of displacement.’ [6]

Froget still sees himself as an African artist. The first untitled work discussed, while depicting the palm tree, still owes its influence to the African mask, which is more evident in Untitled 2 (2023).

In the artist's next artwork, I see red streaks surrounding a blue circle resembling the moon, alongside a black sun and expressive splashes of yellow and brown, creating complex spaces. There is also a hand reaching down, complicating things. The idea of a new space emerging within himself persists, yet it seems he has found the necessary materials to give birth to something new and put them to use. He appears to be at the forefront of the art scene in Mauritius, with a dreamlike quality in his works. The artwork features some staple colours, but it also includes an upside-down hand within the moon, incorporating elements of the African mask in this inverted form. This reclaiming of the African mask is intriguing because, while the artist claims it as part of his heritage, he does not allow its particular energy to dominate him. Instead, history itself becomes his medium for envisioning new realities and spiritual dimensions.

Considering the work’s resemblance to a child in the womb, we can speak about the purpose of reclaiming heritage and how it helps us transcend the pathological traps of misplaced identities. Such traps stem from the lack of a solid foundation in discovering the self. Having completed his task, the artist begins to dream of new frontiers in a non-dogmatic manner, working to free both himself and the viewer into a spirit of creation to make art functional. Mbembe in another essay The Clinic of the Subject echoes this sentiment, stating:

The primary function of art has never been to merely represent, illustrate, or narrate reality. It has always been, by its nature, to simultaneously confuse and mimic original forms and appearances. As a figurative form, it certainly maintained a relationship of resemblance to the original object. But at the same time, it constantly distorted and distanced itself from the original, conjuring with it. In most Black aesthetic traditions, art was produced only through the work of conjuring, in the space where the optic and tactile functions, along with the world of the senses, were united in a single movement aimed at revealing the double of the world. In this way, the time of a work of art is the moment when daily life is liberated from accepted rules and is devoid of both obstacles and guilt. [7]

Froget's artistic journey, marked by the concept of 'Art Vandalism' and his subsequent evolution, reflects the complexities of identity and the struggle against colonial and technological domination. His work resonates with the ideas of Mbembe and Stiegler, who highlight the ongoing struggle against colonisation and the importance of not forgetting the past in the face of technological advancements.

Froget's transition from 'Art Vandalism' to creating art from scratch, influenced by African arts and crafts, demonstrates his commitment to building something distinct from the remnants of the past. This process mirrors the nation-building process, where unconscious forces are projected into nature to forge a more harmonious connection to the environment.

The artist's use of pastels on paper and his incorporation of island-themed aesthetics reflect his unique perspective on Mauritius and its diverse heritage. His incorporation of the African mask in inverted forms speaks to his reclaiming of heritage and his non-dogmatic approach to envisioning new realities and spiritual dimensions.

Ultimately, Froget's practice serves as a testament to the power of art in transcending the pathological traps of misplaced identities. By engaging with his work, we can map a world that speaks to the present moment and possible futures. The dreamlike quality in his works, coupled with his ability to free both himself and the viewer into a spirit of creation, make him a significant figure in the Mauritian art scene.

Endotes

[1] Stamenkovic, M. and Froget, G. 2015. “LOVE IS REAL. In Conversation with Gael Froget.” academia.edu. Available online: www.academia.edu/18072400/LOVE_IS_REAL_In_Conversation_with_Gael_Froget (accessed 5 July 2024).

[2] Mbembe, A. 2017. Black Reason. Translated by Steven Rendall. Duke University Press, 127.

[3] Norton, B. 2024. “Our tools shape our selves”. Aeon (1 April). Available online: https://aeon.co/essays/bernard-stieglers-philosophy-on-how-technology-shapes-our-world.

[4] See Norton, “Our tools shape…”.

[5] Stamenkovic and Froget, “Love is Real.”

[6] Personal communication.

[7] Mbembe, Achille. Black Reason. Page 173. The Clinic of the Subject.

Cover artwork: Gaël Froget, Untitled, 2023. Pastel on paper, 29 x 20 cm.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.jpg)

.png)