White Cube/ Stone Cube/ Blue Cube: Inside the tension between the modern, the euro-antiquity and the Afro-present

.webp)

White Cube/ Stone Cube/ Blue Cube: Inside the tension between the modern, the euro-antiquity and the Afro-present

By Bronwyn Davis

Before arriving at Shepstone Gardens, one inevitably has to cross over the lengthy Louis Botha Avenue, the chaotic, derelict link between many of Johannesburg’s diverse suburbs. It embodies the stark dissonance of Johannesburg, and acts as an unavoidable reminder of the latent anxiety and economically troubled time South Africa finds itself in. Artist Ntsako Nkuna’s burglar bar leaves in ‘Fence to Face’ (2024) serve as a reminder of this outside reality as one escapes into the ephemeral fantasy of Shepstone gardens, filled with delightful contemporary moments in African Art.

In the early, golden hours of the dry Johannesburg morning, the walls are full and the floors sit empty. The art is frozen in a moment of existential dread, for does it exist if there are no eyes to gaze upon it? No wits to engage its proposed conceptual conundrums? The thought is fleeting as the hundreds of feet once again begin to fill the floors. Amidst the autumn-tinted vines spiralling the warm sand stones and stone bricks of the incredibly ornate, yet homey European-countryside-style buildings of the Shepstone Garden estate, I walk through the joyful musings and thoughtful whisperings of the beautifully dressed crowds I pass by, holding their glistening glasses of Aperol Spritz and red wine as the space acts as a backdrop, and they form the mirrors in which the art upon the walls reflects the social.

I cannot help but feel transported into a strange temporal-spatial moment of in-between, stuck in the merging of the romanticised historic and the bright, barrier-breaking contemporary present. The space, the audience and the art appear to be dancing in perfect harmony, all informing the performed and perceived reality of each other.

The 2024 RMB Latitudes Art Fair is like nothing I have ever experienced before. It feels as though it tickles the nostalgic itch of a past we have never experienced, bringing the romanticised Renaissance-esque to the Afro-centric South African present. The contemporary world is undeniably mechanised and often the sanitary white walls and artificial lighting of convention centres and large modern buildings box us into the suffocating artificial disconnect that modernity places between us, each other, and nature. I believe this fresh spatial take on the traditional art fair model reflects our desire as a collective society to re-imagine our moments of gathering to be outside of the white box in a way that connects us more authentically to each other and to the natural world.

Reservoir Gallery, the winner of this year’s Best booth award, shows a body of work that embodies a softness, providing a moment of therapeutic ease with its idealistic photographs, sculptures and drawings. Yet a moment of slight tension and unease is present, amongst the flowing drawings of hard chain links by Bella Rodier, simultaneously fluid, hard and strong. This similar feeling of joy and light with a slight, constant unease remained an underlying theme throughout this year’s RMB Latitudes Art Fair, perhaps reflecting the greater South African art world’s shift from a navigation of suffering to a yearning for comfort and easiness. Both the artists and artworks chosen, and the comforting antiquity of the space were paramount in conveying this dual sensation.

This thematic is similarly emulated in the work of Cinthia Mulanga, who had two works on display, but to which I specifically refer to the digitally rendered moving collage artwork framed within a Samsung TV, housed in the alluring underground hub of Usurpa gallery’s contemporary display of digital art by prominent South African artists.

‘Honey glazed and Good Company’ (2024), is Mulanga’s animated collage of large, well-manicured hands moving the objects and figures of the collage in the same way a child moves around the paper dolls of their doll house, seems to act as a metaphor for a personal or collective lived experience. This is an experience in which one feels as though they have no control, questioning whether this scene is narrated from the figures being moved or the hands doing the moving. This sense of blissful nostalgia and uneasy denial of agency embodies the fair's unofficial theme, expressing a moment of simultaneous love and critique – a hopeful reimagining of one's own life in troubled times. Mulanga is one of the emerging artists intriguingly engaging with the reemerging and reimagined mediums of collage, mixed media and sculptural tapestries, all of which are the new kids on the block, sitting next to the traditional paintings, prints and photography that tend to be awarded the most prestige.

Elsewhere in the fair, Colijn Strydom’s signature pallet of soft pastels sits across his variably sized works, all of which show familiar scenes of domestic life, with nature and people visible across them. The two most eye-catching works are a large picnic scene and an expressive still life of a flowerpot and rainbow, reminiscent of popular illustration styles. At a glance, they depict the beautiful and the nostalgic, yet a closer observation of the picnic work reveals an underlying pathology, and the blue that initially felt calming begins to create an atmosphere of sickness, as one realises all the figures are covering their faces, and the flowers in the blissfully colourful flowerpot are wilting. Both symbols represent the conceptual musing of the sneeze that underlines Strydom’s body of work.

Reservoir Gallery’s curation of Michelle Mathison’s galvanised steel sculpture, ‘Half Moon’ (2024) is the perfect example of the space and the masterpiece merging to create an immersive experience within which the viewer becomes the art, as the semi-circular Namibian marble of his sculpture inversely reflects the polished, foreign marble lining the floors.

It is undeniable that the artworks hung upon the raw walls of the towers, halls and spires gain a sense of character and belonging that white cube spaces rarely provide. Would one respond similarly to the paintings and material sculptures adorning the walls of the galleries of Smtng Good, Loft Editions, Makamo Studios and Occupying the gallery, if they were placed upon the white walls given to the Kalashnikov’s, Gallery Uhuru’s and Candice Berman’s?

The answer to this question may present itself in the form of Occupying the Gallery, whose walls were loosely and playfully covered in card paper, a medium often associated with process work and a moment of incompleteness in artistic practices. The way they physically ‘occupied’ the gallery meant that regardless of the building or wall that housed their work, one would have maintained a powerful reaction to the curation of the body of work with its intentional and literal rejection of the white cube. On a conceptual level, too, it serves as the rejection of white, western conventions of neat, controlled and deeply formal displays.

The artworks adorning the wall are reasonably affordable prints and photographic images, many of which, to quote Chabani Manganyi, begin to embody the deeply nuanced and varied being-black-in-the-world South African experience. A print depicting bread playfully toys with the notion of objects with culture, a photograph by Ngoma Kamphahlele shows two arms handing a vinyl cover of Coleman Hawkins to each other through the window of a dully lit building, titled the ‘Creation of Adam’.

I cannot escape the sense of irony, when the beautiful, engaging and welcoming RMB Latitudes Art Fair’s escape of the white cube took them back centuries to the ornate displays of the Renaissance. A lifestyle one cannot help but admire, cannot help but yearn for in fragile moments such as these. It is as though to escape the clutches of modernism they ran into the arms of antiquity. This irony is lined with an unmistakable sense of absence, as one looks around trying to see the Afro-centric, Afro-modern and perhaps even Afro-futuristic the notion of “going beyond the white cube” seemed to suggest. Regardless of the space, an incredible number of the artists embody the Afro-present through their contemporary experimentalism, revolutionary mark-making and provoking musings, all reimaginings of modern African art truly outside of the white cube.

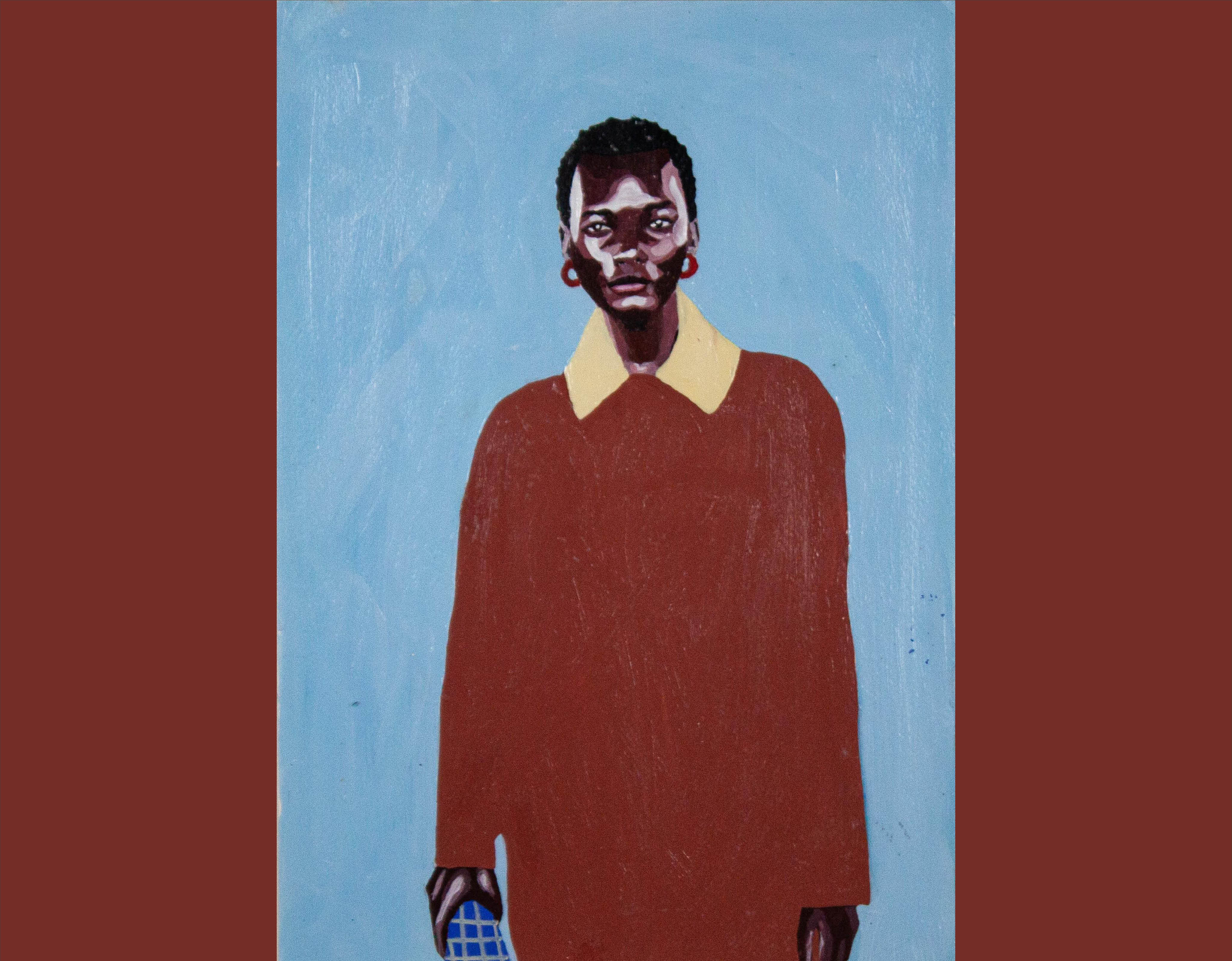

Strauss & Co display their incredible collection of infamous South African artists, and seeing these works by Pemba, Sekoto, Stern and Pierneef trigger the same awe that seeing one’s favourite celebrity would. Yet the excitement of the fair seems to lay elsewhere, parallel to their booth. The blue wall holding the bright, commanding portrait of a middle-aged South African woman by Bambo Sibiya captivates the attention of every single art enthusiast and fair goer that walks past. The backdrop of stencilled patterns in modern colours and contemporary organic pink shapes of Ngemva Kokaqubuka – After Precarity frame a portrait of immense importance and strange familiarity, which he has captured with great authenticity.

Many a passerby stopped and stare until tears start to well in their eyes, as they feel a sense of connection, a sense of awe and a sense of achievement, to see an ordinary, beautiful-in-her-own-right middle-aged black South African woman staring back at them. I hear people start to cite their own memories of their aunties and mothers, strong, stern yet approachable, dressed in incredibly ornate clothing, with a hairstyle another passerby remarks, “that every black girl has had, and we know how good we felt in it”. Sibiya’s work, much like the booth Occupying the Gallery, feels like a true occupation of the gallery space, a true emerging of the rejection of the white cube in search of the blue cube of the Afro-present.

This article was produced as part of the ARAK x Latitudes Critical Art Writing Workshop led by Ashraf Jamal over the course of the 2024 RMB Latitudes Art Fair.

Writer’s biography:

Aspiring artist and curator of creative experience, Bronwyn Davis took their first breath in the loving arms of Colleen (then a nurse) and Ross Davis (then a teacher) in August of 2001, cradled in the city of Johannesburg. A painter, photographer, and coder by training, Bronwyn is currently completing their bachelor's in Fine Arts and Sociology at the University of Witwatersrand. Her creative practice and writing switches between the figurative and the abstract; between the underlying hierarchical fabrics of society, to the escapism of sentimental beauty; to the de-binarized forms of politicized self-expression to using figurative representation of the female body in order to re-position it within our sociological imagination.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.png)