A QUIET MIRACLE: THE ARAK COLLECTION IN SHENZHEN, CHINA

.jpg)

A QUIET MIRACLE: THE ARAK COLLECTION IN SHENZHEN, CHINA

Ashraf Jamal

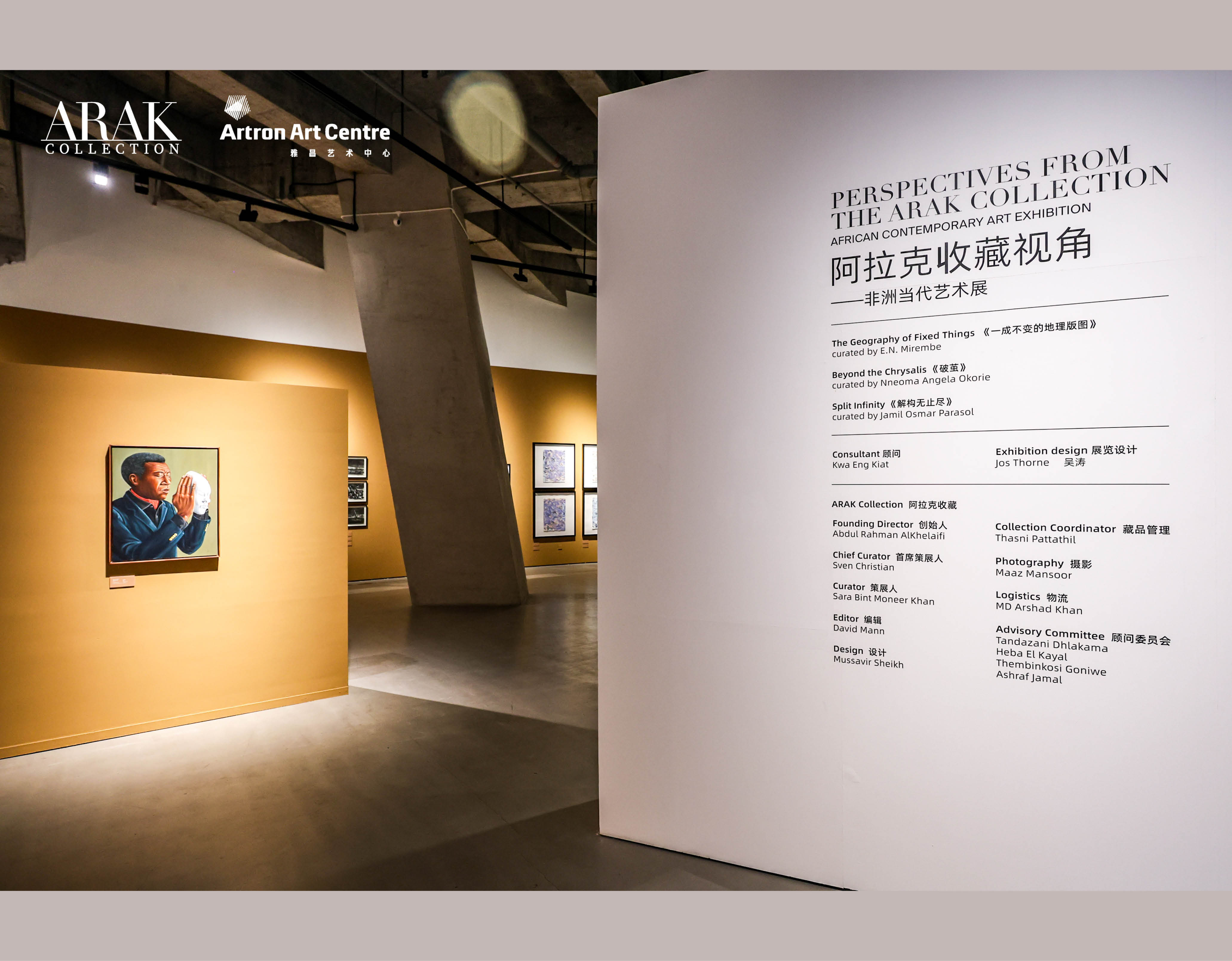

Between 29 March and 29 June, selected works from the ARAK Collection are on show at Artron Art Centre in Shenzhen, China. The works on display are the fruit of three curatorial projects by ARAK Curatorial Fellows—Jamil Osmar Parasol (Split Infinity), Nneoma Angela Okorie (Beyond the Chrysalis), and E.N. Mirembe (The Geography of Fixed Things). Jointly, these exhibitions serve as a seminal cultural dialogue. Given the uniqueness of each exhibition and the singularity of the curators’ respective visions, there is no desire to promote a unified perspective. Indeed, under the umbrella title, “Perspectives from The ARAK Collection,” the approach is at once inclusive and tangential. After all, as Friedrich Nietzsche reminds us, in the perception of art and culture there are no finite facts, only varied interpretations.

In his Steve Biko Memorial Lecture in 2012, the celebrated Nigerian-British novelist and poet, Ben Okri, shares this view. In effect summarising the multiple perspectives adopted in the ARAK exhibition, Okri reminds us to ‘Pass on the word that there are three Africas, the one we see every day; the one that they write about, and the real magical Africa that we don’t see unfolding through the difficulties of our time, like a quiet miracle.’ This faceted understanding is immediately apparent on visiting the exhibition. Parasol, a video gaming specialist, is interested in the reinventive power of illusion, the miraculous power of virtual projection. For our artists are not only the sum of our history, but empowered beings who understand the strength of art as a dreaming tool. For Okorie, on the other hand, it is the materiality of creativity and its spatial location that matters—the innovative use of waste and surplus, the power of abstraction to overcome deficit, and the imaginary power of a sense of place that not only anchors us, but allows for a greater cosmological union. For Mirembe, however, it is the shiftless and shifting nature of objects and beings that compels; the realisation that human life and material culture are intrinsically nomadic. In every exhibition, what is refused is prejudicial dogma regarding Africa. One is acutely aware that the ‘everyday’ can be seen afresh, that the miraculous is located inside of Africa’s historical burden.

%20(1).jpg)

As the leading Chinese art historian and curator, Mr Wang Chunchen, informed us during the talk series, “Confluence”, China’s vision of Africa has always been deeply connected to the animistic force embodied in-and-through the wooden mask. A mediumistic tool, the mask is precisely Okri’s ‘miracle’, the means through which borders are crossed and divisions overcome—in which confluence is possible. ‘A junction of two rivers’, a confluence is an apt metaphor for the exhibition and the two-day talks programme that was held over the opening weekend. Above all else, what mattered—through simultaneous translation—was a deep cultural dialogue about and between worlds. The questions raised and the conversations extrapolated on, concerned “Why African Art Matters in China Today”, why collectors must embrace diversity, why the written word matters in order to anchor visual culture, why technological innovation is vital, and why trade between Africa and China must be on-going. For without mutuality and connectivity our world, founded on what Paul Gilroy termed a ‘planetary humanism’, will be at risk.

.jpg)

It was evident, in the talks programme, that what was needed was the promotion of a post-colonial vision of art and culture ‘for a new era.’ For this to become possible, ‘stereotypes’ about cultures, societies, and nations needed to be productively reevaluated, and that what we urgently require is ‘a new knowledge production of African art’ in a global context. That ‘communication between China and Africa’ needs a more open-hearted accentuation. That a more ‘subtle fabric’ is required in order to understand the interconnection of hemispheres, worlds, nations. If imperialism and colonialism were challenged, it is because of the ‘erasure of local tradition and culture’, the ‘generation of a generic sameness.’ Here, the spirit of Edward Said loomed large, for it is this Palestinian historian and cultural analyst who, in the 1970s, in his book Orientalism, first questioned the West’s ‘occidental’ imperial arm, and its damaging impact on cultures worldwide.

.jpg)

Overall, through the exhibition and talks programme, the shared vision was one of mutual understanding and respect. No attempt was made to override the unique differences within and between cultures. Rather, what mattered was the facetted beauty and wonder of life and art. If Ben Okri’s view is profound in this regard, it is because he never seeks to contain or explain the rich complexity of life; because for him, as it is for those who participated in a historic event in Shenzhen—the artists and curators, the logistical and installation team, the speakers—it is engagement and connection as a quiet miracle that lingers, and stays.

.jpg)

All photographs courtesy of Artron Art Centre.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)