On Maliza Kiasuwa: Stop when you have nothing more to say

On Maliza Kiasuwa: Stop when you have nothing more to say

Nneoma Angela Okorie

Jafar Panahi’s 1995 film The White Balloon is wrought with interlaced brief encounters of characters arriving and departing, the ebb and flow of emotional responses, bookmarked by, if you allow it, the journey as your own silent guide in the background watching the story unfold. A film shot intuitively in real-time opens with a frantic mother looking for her child. The story trundles on from there, but it is when Razieh, the protagonist, loses her money for the first time that it truly engages your attention. Without any twists and a flow of protracted events, we see Razieh's journey end in triumph.

This is often the case with slow cinema, which happens to be a favourite genre of mine. Slow cinema or contemplative cinema strips the spectacle and focuses on the essence of the story being told. Maliza Kiasuwa's approach to making reflects a similar, visceral stripping down—a series of forward and backward movements with an indiscernible pattern, with infinite attention reserved for the in-betweens, leading to symphonic results. Her practice is one of compulsion, where creation precedes the concept not tethered to a fixed narrative, and with the expansiveness of her creations, one without restrictions, she presents to viewers multitudes of meaning.

Kiasuwa transverses this expansiveness with ease, willfully steering away from attempts to pin her down to one style or medium—she weaves, stitches, dyes, mends, and is a master of shredding and morphing dissimilar objects, assembling them to create something whole and total. She considers herself the opposite of a conceptual artist, closer to a florist, her work likened to a flower bouquet. An autodidact who is instinctive, Kiasuwa expands the limitations of form, experiments with her sculptures, and with the unification of objects or materials, merges distinct epochs in their creations. Her work not only requires slowing down, it urgently asks for it. It encourages curiosity about what parts hold the work together—what were the negotiations and compromises, what were some of the dead ends and recursions? These were some of the questions that were pertinent as I learned more about Kiasuwa's work.

Kiasuwa was born in 1975 in Bucharest to a Romanian mother and a Congolese father during the Cold War. She was not always an artist. She never went to art school. The Civil War in Eastern Congo, where she served as an emergency nurse, marked the inception of her artistic path. There, she first made dolls for children with recycled materials. Later, she turned her attention to dry pastel chalk. She drew inspiration from her surroundings. As a child, she was very observant; a piece of information she says comes from her parents: ‘You learn to listen when you become a nurse.’ She continues, ‘I think these abilities have made it possible to develop my art, this very instinctive way of working. The place of my childhood is also an obvious source of inspiration. My mother is Orthodox, and my father is Protestant. I grew up with Orthodox masks and icons. I ate Congolese and Romanian food. I speak both languages fluently. For me, to deconstruct and reconstruct everything is to find myself. It is an incredible richness that is a mixture of styles. Sometimes, I say I'm a hybrid artist.’

Her trajectory unveils a vocabulary forged out of her background as a nurse, with her work grounded in her identity revealing the complexities of her upbringing and heritage. Kiasuwa's practice is as much a scrutiny of otherness as it is about conjuring forms that expand the lifespan of discarded objects. She probes her identity as a woman of both African and European descent.

Misconceptions about her masks are common, but to Kiasuwa they represent the inherent duality of humans.

I started this series after the events in the United States and Europe on the Black Lives Matter movement. I found myself questioning who I was and who I wanted to become. My father is Congolese, and my mother is white, so it was an inevitable question. There is an aesthetic, mystical side, and the representations are strong, allowing us to either reveal ourselves or to hide ourselves.

The Last Supper (2017) was my first entry into Kiasuwa's work. The same patterns are evident in Virgin and Child (2017). Symbolism and mysticism run rife in Kiasuwa's work, so naturally, I was curious to know what they represented. ‘I grew up with Orthodox icons and spiritual images,’ she tells me. ‘It seemed obvious to me to deconstruct and redo them in a more contemporary way using geometric shapes found in traditional African art. This amused me so much that my mother said to me, be careful, we do not touch sacred images. This is my representation of the sacred image.’

.webp)

Regarding her future and specific themes or techniques she’s eager to explore in her future projects, Kiasuwa says she will continue to give herself challenges in her work:

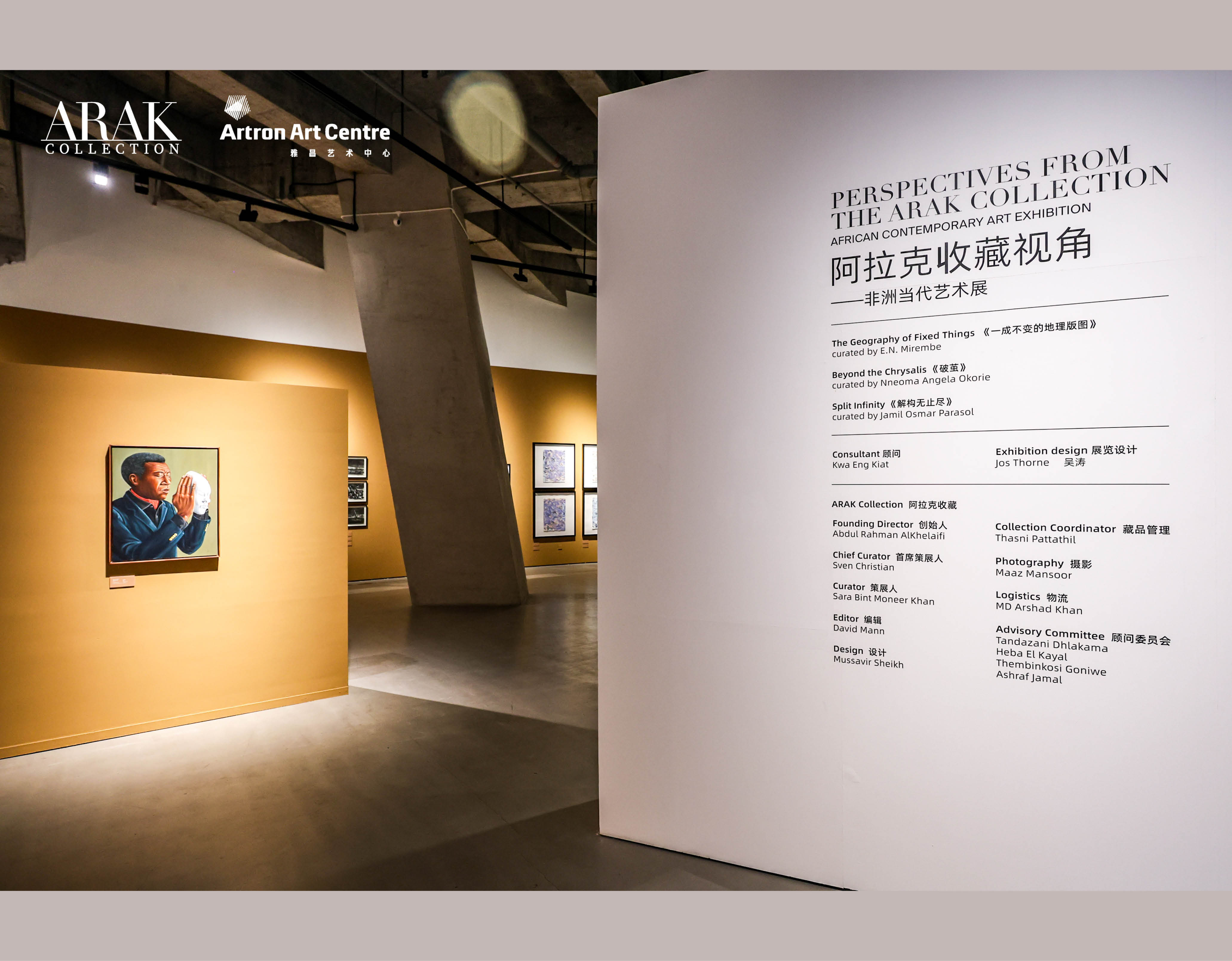

Painting is a way to enter into introspection or meditation… It’s like doodling. It allows me to meditate, calm down, or think about my next work. I am, for that, a nightmare for gallery owners because I take them to places they do not expect. I follow my instinct in creation and not my wallet. Art is a form of expression, and when you have nothing more to say, you have to stop and do something else.A version of this essay first appeared in the exhibition catalogue for “Beyond the Chrysalis” by Nneoma Angela Okorie as part of her 2023 Curatorial Fellowship with ARAK. “Beyond the Chrysalis” is currently on view as part of Perspectives from the ARAK Collection (29 March – 29 June 2025) at Artron Art Centre, Shenzhen, China

Cover artwork: Miliza Kiasuwa, The Last Supper, 2017. Mixed media, 192 x 102 cm

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.jpg)