Bridging Spirits: My First Encounter with RMB Latitudes Art Fair

Bridging Spirits: My First Encounter with RMB Latitudes Art Fair

By Lukho Witbooi

After a 19-hour bus journey from Cape Town to Johannesburg, I arrived at the RMB Latitudes Art Fair held at Shepstone Gardens from May 24th to 26th, 2024. It was the fair's second edition and my first time attending. Remarkably, despite the social anxieties such events typically provoke, I didn't feel out of place. This newfound comfort likely stems from my eight years of writing about the arts, transforming these fairs into spaces where I reconnect with familiar faces. Witnessing the growth of visual arts spaces like Jonathan Goschen's Vela Projects, which opened last year, and Anelisa Mangcu's Under the Aegis, which won the audience award for best booth on the fair's last day, was delightful. However, the real reason lies in the transformative power of art itself and how it reflects our evolving identities. This sense of peace and belonging begs the question: Is it the fairs themselves, the changing world, or just me that has transformed?

As we engage with the art in these spaces, we're drawn to its utility in navigating the complexities of being human. The energy within such spaces is palpable and infectious, triggering profound experiences for the most receptive among us, as it reflects a world where our identities are constantly breaking and rebuilding. While there is light, there is also the spectre of our dark history, a weighty presence that perhaps I am more comfortable with now, standing infused with the collective spirit through genuine engagement with the arts.

This reflection drew me to the past through William Kentridge's ‘Irises, Royal Observatory of Good Hope’ from his debut exhibition in 1979. Kentridge taps into the duality of beauty and darkness, much like my own experience in engaging with history and the future whilst growing up in a post-apartheid era—a world of new opportunities that sometimes, perhaps until our most recent elections, feels devoid of real hope. For me, South African contemporary art has always been a paradox, embodying beauty yet shadowed by the darkness of the human spirit. Kentridge captures this contradiction masterfully.

‘Irises, Royal Observatory of Good Hope’ is composed of lithographs printed on 42 pages scanned from a 1947 Royal Observatory logbook mounted on cotton cloth. The use of these dated pages adds a temporal layer, transforming the artwork into a portal to the past. The black-and-white palette speaks to the era of its materials, creating a timeless quality. This monochromatic choice also resonates with the historical context, making the piece a commentary on time and space.

I am also reminded of a statement from the novelist Masande Ntshanga as he reflects on his experiences growing up under apartheid in the Ciskei homeland capital of Bhisho whilst discussing his science fiction novel Triangulum:

"Apartheid was like a B-movie. This artificial, constructed reality was meant to be convincing, but it was always slightly off, slightly unreal."

But of course, as Nietzsche writes, "The past of every form and way of life, of cultures that formerly lay right next to or on top of each other, flows through us in a thousand waves; indeed, we ourselves are nothing but what at every moment we sense of this flowing."

Thus, it's almost impossible to loosen ourselves from history's grip, and perhaps Ntshanga’s statement was a reflection of an artist living nearer to a time when the marginalised population could begin to dream new dreams.

This tension is why I appreciate Kentridge's work's technical achievement and craftsmanship but am also conflicted. The artwork's focus on nature and outer space can appear tone-deaf, and its craftsmanship seemingly adheres to Western art traditions. This approach is understandable, given Kentridge's background as a white artist, but it also renders the piece a product of colonial art. Its value, driven by these elements, makes me question the context and spirit of its creation.

While valuable and technically impressive, Kentridge's work underscores the disparity in how black artists' histories are recorded and valued globally. Despite its universal appeal – who doesn't enjoy flowers or gaze at the stars and dream? – there remains an element of discomfort. The artwork's detachment from African art traditions can erase Indigenous art forms and spirits, altering the viewer's experience. But later, I learned from Leora’s Maltz -Lega that the artist did not study fine art, but “a combination of African history, politics, and philosophy” and of course the artist went on to have an enduring legacy in using his practice to critique power and injustice.

Kentridge's ‘Irises, Royal Observatory of Good Hope’ speaks to the global imagination and the collective human spirit. Its craftsmanship and evocative power are undeniable, offering a profound commentary on our shared history and aspirations despite the complexities and contradictions it presents.

Transitioning from the historical and the personal, Buqaqawuli Thamani Nobakada's ‘MamGcina Leading The People (1830)’ presents a contemporary reimagining of historical narratives. The piece draws inspiration from ‘Liberty Leading the People’ by Eugène Delacroix. At first glance, one wonders if emulation of Western art represents a quest for validation within established artistic hierarchies. But art is not so simple. It perhaps also speaks to the fundamental realities of the current moment of the visual arts in which the universal appeal and recognition associated with Western artistic traditions amplify the message of empowerment to a broader audience.

The central figure, a black woman waving a white flag while holding a gun, symbolises both strength and a yearning for peace. This juxtaposition challenges traditional representations, reimagining historical archetypes through a modern lens. Nobakada's work addresses the complexities of our identities, but this time through the empowerment and resilience of women.

‘MamGcina Leading The People (1830)’ portrays a moment where history and the present collide. The artist places a black woman in the centre, holding a symbol of surrender and a weapon of resistance. This duality captures the tension and possibilities of the current moment, reflecting a desire to rise above past limitations and seize new opportunities. The surrounding figures look up to her, symbolising hope and the potential for a new era led by the feminine spirit.

Nobakada's piece speaks to a universal desire for progress and transformation. It highlights the intersection of personal and collective histories, where the past informs but does not confine the present. This work embodies a spirit of resilience and renewal, offering a powerful commentary on the role of women in shaping a more inclusive future.

On the last night of the fair, I put on Andre 3000's New Blue Sun, letting the soothing sounds of his flute guide me as I roamed the exhibits. His music, devoid of words, immersed me fully in Sarah Grace's ‘Meditations’ work. Grace's piece speaks to art as a pre-existing substance that shapes our identities, evoking a sense of peace – a pure emotion where thought falls away. This realisation underscored the importance of spaces like the RMB Latitudes Art Fair, where artworks can reflect our transforming identities.

Grace's work is unassuming yet profound, offering a space for introspection and emotional resonance. The piece invites viewers to contemplate their identities and how art can transcend time and intellectual boundaries. It serves as a reminder that art is not merely a reflection of the world but a material through which we can actively shape and understand our place.

\Kentridge's ‘Irises, Royal Observatory of Good Hope,’ Nobakada's ‘MamGcina Leading The People (1830)’, and Grace's ‘Meditations 2’ exemplify the transformative power of art to navigate complex histories and reflect evolving identities. They highlight the contradictions and possibilities within our collective human spirit, offering profound commentaries on our shared past and future. Through such diverse works, the RMB Latitudes Art Fair becomes a space where these dialogues thrive, fostering a deeper understanding and connection among its audience.

The RMB Latitudes Art Fair offers more than just an exhibition of artworks; it provides a platform for exploring and understanding the ever-changing landscapes of our identities. Through the works of Kentridge, Nobakada, and Grace, we witness the power of art to bridge the past and present, the personal and the collective. This fair stands as a testament to the enduring relevance of art in shaping our understanding of ourselves and our world. In these spaces, we find reflections of our history and the seeds of our future, growing from the fertile ground of creativity and shared human experience. As we engage with art, we remain connected to the spirits that drive us forward, ever-evolving, ever hopeful.

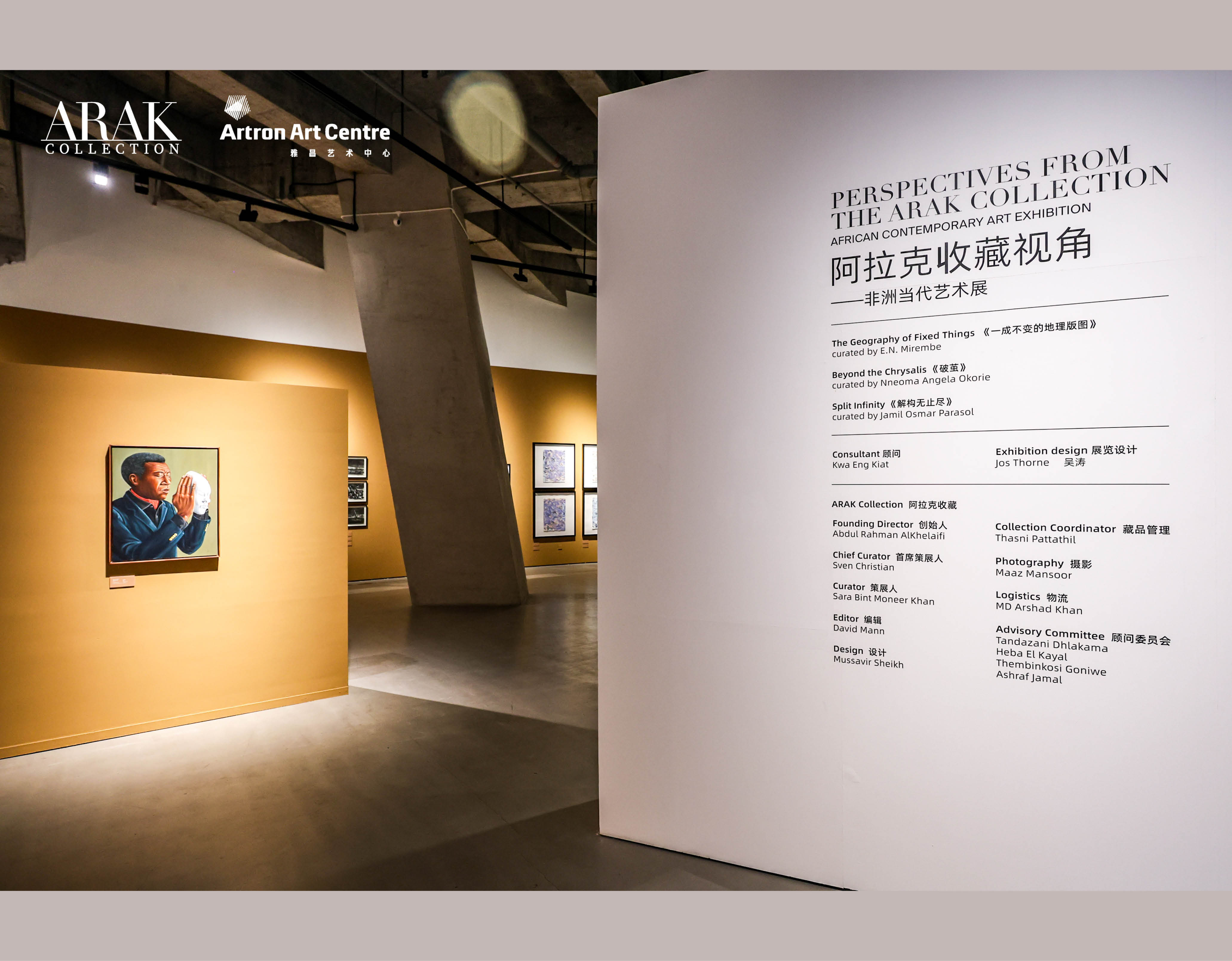

This article was produced as part of the ARAK x Latitudes Critical Art Writing Workshop led by Ashraf Jamal over the course of the 2024 RMB Latitudes Art Fair.

Writer’s biography:

Lukho Witbooi is a South African writer with works published by Art Africa, Creative Feel, FunDza Literacy Trust and The Kalahari Review etc. He is a MA student in Creative Writing at the University Western Cape and was a recipient of the David Koloane Art Writing Mentorship Award at The Bag Factory Artist Studios in 2018. Witbooi is also the former Assistant Curator of Digital Platforms at Zeitz MOCAA.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.jpg)